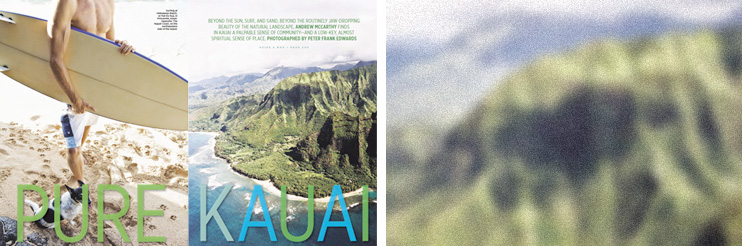

Pure Kauai

BEYOND THE SUN, SURF, AND SAND, BEYOND THE ROUTINELY JAW-DROPPING BEAUTY OF THE NATURAL LANDSCAPE, ANDREW MCCARTHY FINDS IN KAUAI A PALPABLE SENSE OF COMMUNITY—AND A LOW-KEY, ALMOST SPIRITUAL SENSE OF PLACE.

By Andrew McCarthy

“I thought you’d like to sit out here, so you can watch the traffic go by,” Auntie Rose suggests, offering me a chair.

“Thanks, Auntie. But do you mind if I sit over on this side and look at the mountains?”

She smiles, shrugs, and turns to go. I take a seat and settle in on the porch out front of Wrangler’s Steakhouse, in Waimea, on the southwestern coast of the Hawaiian island of Kauai. I’ve become a regular at Wrangler’s—never mind that there are few other options for eating in town. Auntie Rose (auntie is a Hawaiian term of respect and affection, one not limited to blood relations) is a tiny woman with large glasses over dark eyes. She’s taken me under her wing. Her offer of a prime seat to watch the action along the street shows just how much she cares.

Across the way is the Waimea Hawaiian Church—Sunday services said in Hawaiian. Down the street is the local cinema— five showings weekly. A few pickup trucks hum by on the twolane Kaumualii Highway. Same as yesterday. I’m beginning to get the hang of this particular island.

I know Hawaii pretty well. I had a house for 10 years on Maui. I trudged across my share of lava on the Big Island. I partied in Honolulu, golfed on Lanai, and slunk around insular Molokai. But Kauai remained off my personal radar—until now. The oldest and farthest west of the major Hawaiian Islands, Kauai bubbled up from the ocean floor 5 million years ago. Roughly circular in shape and covering more than 550 square miles, the island is sunbaked and dry in the south and west, while the north is lush and green. Dictating this weather pattern is Mount Waialeale, at the island’s center, which traps the passing clouds and often gets more rain than any place on the planet (460 inches annually).

On the bluffs above the eastern tip of Hanalei Bay, on the Eden-like North Shore, I look out on a near-perfect crescentshaped beach. Tireless waterfalls spill from jagged cliffs in deep green valleys. Clouds hover and vaporize, altering the light, changing perspective. It is, simply, the most dramatic vista I have seen anywhere in Hawaii. Stephanie Kaluahine Reid, the 10th-generation Hawaiian standing by my side, takes it a step further. “It’s not a physical thing,” she says. She looks out over the deep blue bay. “It’s a sense of connection to the place. I feel rooted here.” I understand her meaning as much as a nonnative can. Perhaps that’s why I always feel like a better version of myself when I’m in the islands, and why I keep returning. A rain shower rolls across the far side of the bay while the sun blazes down on us.

Anchoring this camera-ready spot is the recently renovated and re-branded St. Regis Princeville Resort: 252 rooms carved into the side of the cliff, taking the best advantage of their greatest asset—the view. My wall-to-wall window catches me up short every time I glance out to see Mount Makana. The elegant grounds roll down past the low-key pool to the beach and bay and beyond.

But it’s around the point, along a narrow path, then down a hundred-foot descent, reached by clinging to a fraying twine anchored to a rotting palm tree, that I find a piece of sandy paradise. Pali Ke Kua Beach, known to the locals as Hideaways, is tucked under a canopy of false kamani trees beneath ff0-foothigh black lava-rock walls. At dawn each day, I watch the sky soften and the sea take form. One morning, with the sun not yet over the cliffs, my eye catches something far down the beach. It’s coming up out of the water. A closer look reveals a green sea turtle lunging its way up onto the sand. It’s huge, at least three feet long and several hundred pounds. In the sea the turtle is power and grace in motion, but hoisting itself up by its front flippers and flopping back down onto the sand, making only a few inches’ progress, this is tough going. I settle in for a closer look. The turtle lifts its head to turn my way. We blink at each other. It lunges another few inches up the beach. Sea turtles saw the dinosaurs come and go, but up here on the sand, even under the armor of its massive shell, it seems vulnerable and exposed. We sit silently together, the waves lapping the shore. I relax in its patient presence and feel myself land fully on Kauai. I experience the same sensation I have so often felt in Hawaii while doing seemingly nothing—the feeling that my time is being well spent. As the sun breaks over the cliffs, Itake a morning swim and leave my friend to its solitude while I head back to the mansion on the hill.

Sitting on the Makana Terrace at the St. Regis, watching as the clouds reveal a half-dozen waterfalls deep in Waioli Valley and seeing a double rainbow materialize over the early morning surfers in Hanalei Bay, I find myself thinking: life is sweet. But eventually having my every whim met begins to get under my skin, and I need to move.

Just a few miles along the coast road, past the beach where Mitzi Gaynor washed that man right out of her hair in South Pacific back in 1958, is the most famous of Hawaii’s places to hike. The Kalalau Trail clings to the Napali Coast for 11 untamed miles of killer views and switchbacks. I set out in the sun, soon the wind picks up, then sheets of rain lash down, then sun again. I pass bamboo and ohia trees. Ocean views from vertigo-inducing drop-offs open up. I step across streams and past waterfalls—all within a half-mile of the trailhead.

An hour further on, after rising and falling and twisting and rising again, the trail descends. I can hear the growing sound of running water—the runoff from Hanakapiai Falls. I come upon a hand-carved wooden sign, nailed onto a guava tree.

I get a stronger sense here that nature is still calling the shots than I’ve felt on any of the other islands.

Rock ’n’ roll icon Graham Nash and his wife, Susan, became North Shore locals back in 1976, and they’re well acquainted with nature’s power. “I remember after Iniki….” Susan starts to tell me before her voice trails off. (Hurricane Iniki destroyed or damaged more than half the island’s homes in 1992.) “It’s very precarious out here. Hawaii is the most isolated population center on earth, and we’re at its far edge.” Like so many I meet on Kauai, Susan speaks with fervor about the island. “There’s an accountability here—it’s all about the community,” she tells me from the lanai of their house, amid the guava, banana, and avocado trees. “Even though our family has lived here for over thirty years, we’re relative newcomers,” Graham adds. With views deep up into the Wainiha Valley and out to the sea, they’ve created a low-key, eclectic idyll.

Over on the windward coast, just after the ring road begins to turn south, the sun asserts itself on a more consistent basis and the Anahola Mountains begin to dominate the terrain. Spike-shaped Kalalea Mountain is considered sacred land, and the village of Anahola rests comfortably in its shadow. It was here that the Dalai Lama made an unscheduled visit during his trip to the islands in 1994. “Anahola is the portal where the souls enter the earth,” Agnes Marti-Kini, a longtime resident, tells me somewhat portentously. Marti-Kini and I are on the beach near her house. She asks permission from unseen spirits to bring an outsider to this sacred Hawaiian spot, then offers an incantation. Marti-Kini recently published a definitive book on Anahola, and she’s brought me to see several large lava rocks with circular bowls hollowed into them—“A mano [shark] altar,” she explains. “It was here that the ancestors would leave offerings to the spirit world to ensure an abundant catch and a safe journey.”

Perhaps it’s because the area isn’t developed or built up, or perhaps there are other reasons, but I can feel the power surrounding us on the beach, with the wind ripping, the waves crashing.

A few miles and a world away down the coast, I get lost in the resort development of Poipu. I’d been wondering where all the overbuilding was on Kauai. I found it. It’s sometimes difficult to reconcile places of such unaltered power like Anahola with what’s been done on the South Shore, but it’s a sight common to portions of nearly all the islands—condominiums and hotels battling for beachfront, all natural flow of the land overtaken. This often uneasy coexistence of sacred and profane is something you need to come to terms with if you’re going to spend any real time in Hawaii.

Farther west, the island reasserts itself. Out past Kalaheo, past fields of coffee trees (the last of the sugarcane, once Kauai’s staple, was plowed under in late 2009), the terrain becomes even drier, the sun stronger, and the pace considerably slower. I drive down a deserted main street in the near–ghost town of Hanapepe. Founded by Chinese rice farmers in the late 1800’s, the place has a notorious past, replete with opium dens and brawler bars—those days are long gone. I crawl through the village late in the afternoon: all the doors are closed, except one. The lights in Talk Story Bookstore are still blazing.

Sorting used books, alone inside the plantation-style singlewall- construction building, is Ed Justus. A pale, bearded man with a direct gaze, Justus could be a young college lit professor. He came to Kauai with his wife, Cynthia, from Virginia seven years ago, “because the plane ticket was fifty dollars cheaper than going to Honolulu.” The fit was immediate. “We never left. Never sent for anything. Never went back.”

We stand in the doorway, watching the day decline. Justus exchanges waves with every driver who passes. “The best part of the West Side is you get to know your community, your neighbors,” he says. A battered car with several day laborers rolls by, and the boys inside shout out greetings. “It’s a rugged island, kind of like the local culture. Respect it, and it’ll respect you.”

Although each of the Hawaiian islands garners its own loyalty, what I’m seeing here on Kauai is different. Twice, Kauai withstood assaults by King Kamehameha to take the island by force. More recently, in 2007, about 100 locals leapt into the water at Nawiliwili Harbor to prevent the unwanted interisland Superferry from docking on its maiden voyage. The ferry idea was abandoned.

That kind of pride is evident on the neighborhood level as well. In the westcoast town of Waimea, 81-year-old Nancy Golden—founder of the local familysupport center Nana’s House—tells me: “The West Side is what the whole island used to be like.” Waimea was once a home to Kaumualii, Kauai’s last great king, and it was here that Captain Cook first set foot on the Hawaiian Islands in 1778. (He was killed a year later by locals on the Big Island.) It’s got everything I need in a Hawaiian town—a friendly, authentic local scene, a few decent restaurants, and a Hawaiian place to stay. The Waimea Plantation Cottages are exactly what the name suggests: 61 former sugar- plantation cottages refitted as guest accommodations. They are scattered around 27 acres of wide lawns, where groves of ironwood and coconut palms, empty hammocks, and several massive banyan trees anchor and preside over the land. The place is pure old-school Hawaiian “aloha.” I suppose I could imagine a more comfortable spot, but why try?

The days begin to roll by unaccounted for—a hike up in Waimea Canyon State Park, a swim at a deserted stretch of beach in Polihale State Park, watching the local kids play an evening game of baseball. And then I’m on the porch at Wrangler’s Steakhouse for an early dinner, just like I was the night before. Auntie Rose greets me by name, and I settle in and look out beyond the green corrugated-iron awning of the Big Save market across the street and up into the foothills of Mount Waialeale. The clouds are briefly pink, then give way to an uneventful gray as the sun fades behind me. The few tired streetlamps come on. A pickup truck eases past. The night falls silent.

I remember back on the North Shore Stephanie Kaluahine Reid had talked about the feeling of unity on Kauai and the Hawaiian word she used for it, “kakou—the power of we.” And that’s been my experience here, from the Nashes up north and Agnes Marti-Kini, in Anahola, to Ed Justus in the west and dozens of others. That strong sense of community, of “us”—it exists on all the islands, but here I’ve found it to be a dominant force, a motivating code. It’s something that exists beyond the mere physical beauty, and goes to the heart of the island and the commitment people have to it, and to one another.

Auntie Rose returns. She tells me that the daily specials are the same as the day before. Then she leans close and confides, “I thought you’d be back tonight, so I had them put aside an ahi poke appetizer.” It’s all I need to hear to feel Kauai’s pull.