Chat Rooms

Dublin’s pubs offer camaraderie and community—even without a pint.

By Andrew McCarthy

The problem with a pub crawl in Dublin,” native son Conor Smyth laments, “is that instead of checking pubs off the list, the list just keeps getting longer.” Bellied up to the bar at Devitt’s Pub beside him, I consider this wisdom and nod my head vaguely. The weight of Conor’s realization settles heavily upon us. He drains his pint. I chug away on my Ballygowan sparkling water, and consider the daunting task I’ve set myself.

I’m deep into a grueling, self-imposed quest to find the best, most authentic, most truly “Irish” pub in Dublin. I’ve been at this thankless chore day after day, night after night, for nearly a fortnight, and the magnitude and complexity of my mission is beginning to truly register.

The fact that I don’t drink might, at first glance, appear to disqualify me for such reconnaissance. But I beg to differ. Sure, the pubs in Dublin serve booze—and plenty of it—but they’re also serving up something else, something that has made the Irish pub legendary, and much imitated, around the world.

The warm welcome, the sense of community, and camaraderie help to ensure that the vibrant oral history of a people is relived and renewed each night. It’s a history that gathers to create a unique culture centered around “the chat” and a common sensibility. And that’s what I’m after. With my clear head, I won’t quit until I find it— in its purest form.

I’ve deep roots in Ireland, with dear friends and family here. I come back often.When word of my mission spreads, I’ve no shortage of volunteers to join me in my quest. Make no mistake, this is no solitary Hero’s Journey; this is a social outing.

Colm Rice, one of Ireland’s finest potters, leads me to his “local,” Slattery’s, out near Ring’s End. “It’s always my first port of call,” he assures me as we settle into a corner banquette. “You get a good easy mix here.You got your pensioners nursing their pints; you got professionals and thugs sideby- side.You got football on the TV, you got people who know you.” He refers to the low lighting and candles: “And you got romance.What more could you want?”

Then Colm turns and points out the large window that overlooks the tables outside. “And on a winter’s evening, the sun sets directly down the center of that road and shines through this window right here,” he says. “And for exactly two minutes each day, it lights up this whole place in a golden glow like Stonehenge on the summer solstice.” (In case anyone was concerned, the blarney still runs thick in the Dublin pub.)

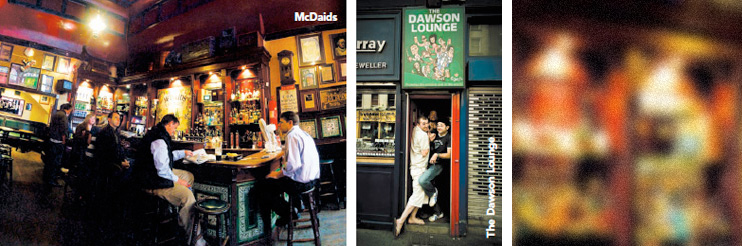

Later, joined by more friends who gather and then drift away, only to be met by others, I find myself in the city center, near Grafton Street, where so many of Dublin’s most famous, and finest, pubs are within stumbling distance of one another. The Edwardian pub Neary’s, on Chatham Street, has a rumpled, artsy elegance I find easy to fall into. The door to the alley behind it is open, and the music and thundering feet from Riverdance, playing at the Gaiety Theatre across the alley, provide a soundtrack. Around the corner, McDaids lures the literary crowd. Irish writer “Brendan Behan drank here,” I’m told. (I’m told this in nearly every pub I enter.)

Over on Merrion Row, the boys at O’Donoghue’s keep the traditional Irish music ripping every evening. “This would be the strongest Trad music in town,” local resident Peter O’Brien assures me between sets.Without doubt, the most photogenic pubs in Dublin are two Victorian gems—The Long Hall, on Great George’s Street, and Ryan’s of Parkgate, across the River Liffey. But it’s Kehoe’s— established in 1803—on South Anne Street that gets my attention among the city center pubs. A sagging Victorian charmer, it has a quirky, individual appeal, with a few “snugs” (partitioned areas originally built for privacy) and an inviting upstairs den. I find myself returning here again and again during the course of my research.

The thing about the Irish pub is that it takes on different personalities at different times of the day. I bring my kids over to The Stag’s Head, with its elegant stained glass and beveled mirrors, for a lunch of fish and chips. “They’re very welcome here,” the girl behind the bar assures me, and my 8-year-old son and 4-year-old daughter happily run riot between the tables and turn the coasters into flying projectiles. At night, this same pub overflows onto the street with university types explaining away the death of the Celtic Tiger.

Another evening, I’m on a narrow, winding lane leading high into the Dublin Mountains (but still technically a part of the city). I’m headed to The Blue Light Pub, a simple, whitewashed stone structure. It’s a rustic spot with a slate floor and an open hearth. The farmers and country folk who fill it remind me just how quickly the sophistication of the city is left behind in Ireland. A few women munch from a bag of chips and watch Fair City, the long-running Irish soap opera, on the television above the bar. Men share a smoke outside. Little happens at The Blue Light in terms of action. Louise Horgan, a Dublin native, explains, “It’s a ‘pint a Guinness pub,’ none of your messin’,” and it’s got an easy, uncomplicated feel. Later, a burly man with unruly white hair, who has been silent and nearly invisible all evening, begins to sing, unaccompanied, and without warning. In a tremulous tenor, he recounts a rambling lament of lost love and riches—

“She gave me her favors, and I gave her my word.

But, there’s gold in the valley, there’s gold in the sea . . . ”

He falls silent as abruptly as he began and disappears back behind his eyes. Suddenly the small man beside me breaks into “Chattanooga Choo-Choo.” (It’s getting weirder by the minute.) As he finishes, all eyes turn my way. Apparently, I’m up. It’s the only moment of my extended pub-crawl when I wish I drank. In fact, I wish I were drunk. One halting verse of “Love Me Tender” later, I sheepishly slink to the door, but not before handshakes all around.

Back in the city and a world away, I take refuge in the smallest pub in Dublin. Down a flight of stairs, The Dawson Lounge, off St. Stephen’s Green, is an elegant wood-paneled den with just six cramped bar stools and three cocktail tables. You could disappear here.

But I’m on a mission.

And it’s becoming increasingly clear that this is a very subjective survey. Everyone I meet, everyone who accompanies me on this sojourn, has an opinion. There are as many favorites as folks. Clearly, there is no one most authentic Irish pub. As for myself, I’ve learned that the watering holes that capture my affection most are not the fancy or the famous, but the local spot, the corner pub, the place you could pass right by without a thought. It seems that what touches me is more a vibe than any specific place.

On the last night of my odyssey, I find myself far from the flashy “super-bars” that sprang up in the last decade, or the well-known pubs of Joycean Dublin. I’m at a local joint in Ranelagh—one of the many villages that comprise Dublin—at Birchalls Pub. It’s nothing fancy, just a Victorian local pub.

It’s raining. Friends begin to arrive. The pub begins to fill, and you can feel people settling in for an evening of fellowship and the chat. “The pub is shelter from the storm, always has been,” Karen Griffin, another Dubliner, explains. “You can feel it in here, the feeling of years of hospitality and warmth, the relief of arrival. You feel the history of Ireland in a pub like this.” More friends arrive. Tables are pushed together. More pints (and more sparkling water) are consumed. The room hums with the sound of voices and clinking glasses.The rain beats down outside. And there’s nowhere else in the world I’d rather be.