In Ireland, Optimism is in the Air

Bust, then boom, then bust again. Now the Emerald Isle is finding its way back.

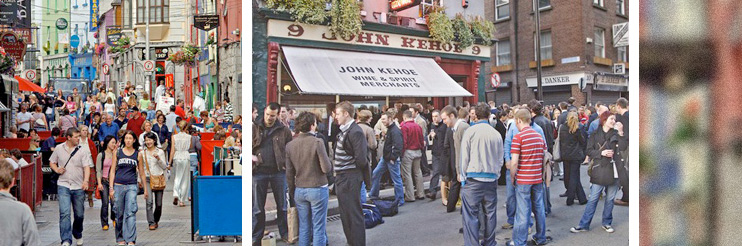

Left: (Richard Derk) The pedestrian mall in Galway is a busy, bustling place. Right: (Stephen Saks / Getty Images) People drink on Grafton Street after work outside of John Kehoe, a very popular pub that often draws a crowd that spills out to the street.

By Andrew McCarthy

DUBLIN, Ireland — There are no people on Earth as romantic as the French. No one is punctual like the Swiss. The Germans have defined a sense of order. The Italians know how to eat. And no one, I mean no one, does misery like the Irish.

Ireland’s well-chronicled story of rags to riches to rags again is a cautionary tale of the early 21st century. A country reared on hardship, famine and oppression has, after a brief turn in the economic sun, been cast back into the misty gloom of struggle.

But lately I’ve begun to notice that a mischievous quality has sneaked in under the cloak of misery the Irish have put back on with disarming ease after the good times ended. There is still plenty of suffering to go around, but the place has begun to get a buzz about it again — one that reminds me of the country I knew and loved so well.

I first landed in Ireland 25 years ago, and as it is today, The Misery was on the land. The ’80s were a dreary time of inflation, double-digit interest rates and a stagnant economy.

Yet the very direness of the situation swung doors wide to me that might never have opened had the people’s necessity not dictated. I paid strangers just a few pounds to sleep in their spare rooms. I ate breakfast at the family table and in the evening watched the Rose of Tralee beauty contest on a black-and-white television beside a mother and father with a vested interest.

Of course, I drank too much in smoky and welcoming pubs, and I played bad golf on wild, spectacular and deserted courses. For a few hundred dollars I joined one such club in Lahinch, and to this day I receive my annual bag tag, one of my most prized possessions.

I returned to Ireland every year — until I missed a year, and then another, and then nearly a decade had passed. When I finally returned, the economic upturn known as the Celtic Tiger had begun its voracious assault on the land — a change that seemed at first as miraculous as it did unlikely.

Changing fortunes

Within a few years at the turn of this century, Ireland began to transform from a charming bog to the poster child of European Union dreams. Farmers put down their beloved Guinness and picked up Pinot Grigio. Dublin morphed from a dank backwater into a sophisticated metropolis. Helicopters were chartered to fly across the country for a lunch of fresh Galway oysters at Moran’s, and then back to the posh suburb of Dalkey in time for dinner. Property prices soared, and credit was easy. The going was good.

I too succumbed to the fever that was gripping the land and bought a home. Yet from my outsider’s perspective, something in the auld sod was being lost along the way to prosperity. The pubs banned smoking, but the warm welcome also seemed to go up in smoke. The playful twinkle in the eye and the friendly slag were replaced by an aloof disinterest. The good-natured blarney had become boasting bluster.

Neither people nor countries get rich quick gracefully, I concluded. I was glad the Irish were finally having their moment in the sun, but for me, the place had begun to lose its magic.

And then it all went to hell. Seemingly overnight, housing prices plummeted (and are down 55% from their height in 2007). Unemployment recently hit 14.9%. Many of the Eastern European laborers who had flooded the land have gone home.

The Irish have been left alone to nurse a vicious hangover.

Yet in the midst of all this hardship something strange has begun to happen: The restaurants appear packed again, pubs are overflowing onto the street, there’s laughter around town. Could the Irish really be rising up and dusting themselves off?

Is this just wishful thinking on my part — a desire to recapture an earlier time of innocence? I decide to head to the one place in Ireland a man goes when looking for answers to life’s bigger questions.

At the bustling bar in Kehoe’s Pub on South Anne Street in Dublin, the Guinness is flowing and the chat is in full swing. On first glance, not much has changed since the gold rush days of 2004.

Dubliner Jim Lyng sets me straight. “We completely lost the run of ourselves during the boom,” he tells me. Then, sounding like the psychologist he is, Lyng continues: “No one trusted it could last, and in a certain way it was a relief when it finally burst. And what’s happening now, with the struggle again, in a certain way we love it — I’m not talking about the people who paid too much for a home and can’t afford their mortgage — but there’s something in who we are as a people; we’re comfortable with struggle.

“We’ve come home to ourselves.”

Perhaps that feeling of regaining something lost during those heady days is what I had begun to notice. I hear that sentiment echoed again and again around town.

“There’s a sense now that we’re all in this together,” Dublin native Louise Horgan says as she strolls past the small Victorian row houses in the now trendy Portobello section of town. Beside a shuttered church, Horgan points to a thriving community garden planted beneath the “For sale” sign. “This garden is a direct result of the downfall,” she says. “It didn’t exist before. There’s a palpable sense of community now.”

There’s also a sensation around town that people are doing more than just making the best of a bad situation. The city center seems alive in a way that feels almost counterintuitive. New businesses are opening; an entrepreneurial spirit appears to be taking hold.

“I never could have done what I’m doing during the boom,” John Farrell says. “The bust gave me the opportunity.” Reared in the poverty-riddled Ballymun council flats of north Dublin, the brown-eyed 38-year-old recently opened his third restaurant in the last four years.

“I bought my first place when it was in receivership in 2009,” he says. “It would have been eight times that cost during the boom — I’d still be clearing tables. Back in the Celtic Tiger days, it was the same people opening the same kinds of places. But now, there’s a whole new generation; it’s very exciting. You can feel it.”

Farrell’s latest venture, a Mexican restaurant named 777 on South Great Georges Street, is testament to that spirit. It’s funky glitz ‘n’ kitsch in design, consistently packed — and with the Margarita Especial made with organic tequila priced at 12 euros (about $15), it’s not cheap.

“People are still willing to pay for the small pleasures,” salon owner Noel McCarthy explains. “We put our foot in the water of prosperity and decided we liked it. People don’t want to give everything up. If you’re in the housing or the car business, forget it, but the small-ticket items are booming again.” In what is perhaps a barometer of the times, McCarthy owns two hair salons, down from five during the height of the boom, but he plans to reopen a third in the next few months.

“You still got your taxi drivers moanin’ and groanin’, but they were complaining during the good times too. It was all a little unreal before, but now we’re back to the graft, and we’re good at that. An hour’s pay for an hour’s work. We’re in a better place now.”

A walk down a swarming Grafton Street — the pedestrian mall and hub of Dublin’s shopping center — past Trinity College, across the River Liffey and up bustling O’Connell Street, seems to bear out what I’m hearing. I begin to wonder if this new optimism is restricted to the big city or if they are feeling a similar sense of resurgence in the country.

Reality check

I head west on the M6 motorway, covering ground at a rate that would have been impossible just a decade ago, before EU money established a network of highways throughout the country, making obsolete many of the notorious meandering Irish lanes.

My first stop — just outside the postcard village of Cong in County Mayo — is at one of the favorite playgrounds of the Celtic Tigers. Inside the wrought-iron gates I glide past the golf course and sweep over the gentle rise until the view of Ashford Castle stops me in my tracks. Dating to 1228, later owned by the Guinness family, the soaring gray stone turrets and formal gardens, home to Ireland’s oldest falconry, Ashford became a symbol of Ireland’s excessive success. And to look at the manicured lawns and full parking lot, the genteel life at Ashford continues.

“At the high-end level, there is huge demand,” general manager Niall Rochford says. “If I had more suites, I’d be filling them every night.” Yet the once-bustling heliport sits empty. “We used to need air traffic control out there; choppers were circling and hovering. But I can’t remember the last time an Irishman got out of a helicopter. We’ve all come back to a level of reality.”

Rochford shrugs and then leans toward me. “We lost some of the caring that the Irish are famous for,” he says. “It’s back to basics, and that’s a good thing.”

After a quiet stroll through the lush gardens and down along the misty shore of Lough Corrib, Ireland’s second-largest lake, I find it difficult to imagine that anything could be amiss on the Emerald Isle.

But the rising tide of the boom did not raise all boats equally. Hardship in the west is keen. I head down the road to the university town of Galway. With close to 80,000 residents, it is the west’s largest city.

Yet here too, the pedestrian mall along Shop Street is — like Grafton Street in Dublin — swarming. A few more street musicians than I remember have their hats out, but the students that give this town its perpetual feeling of optimism are dictating the mood.

An hour farther down the coast, around Galway Bay, past some of the “ghost estates” that litter much of the Irish landscape and into County Clare, beyond Ballyvaughan and along the fringes of the rocky Burren, past whitewashed houses with thatch roofs that preside over sheep grazing in green fields encased by dry stone walls — this is the Ireland of postcards — the village of Doolin is strung along one narrow road that fizzles out down by the sea, where ferries ply the route to the Aran Islands. This is the epicenter of Irish traditional music. I’ve come to see whether they still have a song to sing.

Street life is humming, but Doolin native Declan O’Callaghan sums up what I hear more than once: “At least we’ve got the Americans coming in for the music; otherwise, it’s pretty bad out here.” Yet when the sun goes down, the music starts and the Guinness begins to flow, troubles seem forgotten — at least while the fiddles burn.

Eventually I make my way back to Dublin and ease onto my familiar stool in Kehoe’s Pub, still trying to reconcile the feeling of struggle I know exists with the consistent laughter I’ve heard around the country. Then I remember something my psychologist friend Jim Lyng pointed out at the beginning of my unscientific experiment to take the temperature of the land.

“What you have to understand is that for the Irish our joy is not something that’s subsequent to misery, the way it might be in other nationalities who go through great hardship or tragedy. Our misery and relationship to suffering is so ingrained, so long-standing, so imbued in who we are that it coexists with everything else. Consequently, we can laugh at anything, including ourselves.” Like the good psychologist, Lyng is silent as I consider this. Then he continues.

“There is certainly no promise that things are going to turn around, but on a good day, when the sun is shining and a fair wind blows, I would take a chance and go out on a limb to suggest that there is the potential for hope.”

For a people who love their misery as much as the Irish, it sounds almost like a guarantee.