Ethiopia Underground

Afar spins the globe to pick a destination at random, then tells a writer, “Pack your bag, you’re going to… .”

By Andrew McCarthy

The man who arrested me at dawn in Lalibela was tall and gaunt. His voice was rich and full—and angry. He carried a long staff in one hand and a rifle slung tightly on his other shoulder. He reminded me of an Ethiopian Lee Marvin. It was just the kind of thing that happens when you show up alone in a distant country without a plan.

I’d landed in Addis Ababa, the whirling capital of Ethiopia, at night. I found a simple place to eat. With my right hand I began to scoop beef wat (spicy stew) with injera (spongy flatbread), and in the dim glow provided by a grinding generator (power was being rationed all over the country), I noticed a poster on the wall. The image was a high-angle night shot of a golden-lit, stone church exterior. It looked intriguing; it looked really old.

“Where’s that?” I asked the waitress.

“That?” Her eyes followed my pointing finger. “That’s Lalibela.”

“It looks interesting.”

She smiled.

By noon the next day I was there, more than 8,000 feet up in the Lasta Mountains. The land was parched and brown, with few trees. There seemed little to suggest why the place had been designated a UNESCO World Heritage site, as the waitress in Addis Ababa had assured me it was. People slowly walked the dirt roads, many, mostly women, carrying baskets or water or wood on their heads or backs. I saw mud-and-stick huts, cinder block homes, a primitive cemetery, but no church.

Only when I was nearly upon it did I realize I should have been looking down.

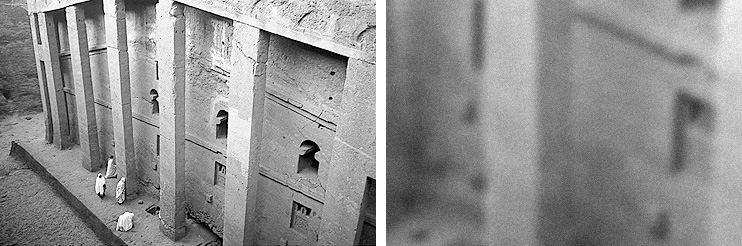

The church—and 10 others—sat below ground level. A complex of monolithic structures had been hollowed out from vast deposits of red volcanic rock—no mortar, no bricks, everything just carved out from the stone. Deep, excavated courtyards that ended abruptly in steep walls surrounded the churches. The only access was by a honeycomb of tunnels and trenches cut into the stone. All this accomplished with hammer and chisel in the 13th century.

The maze of structures was built during the reign of King Lalibela. Legend has it he wanted to create a “New Jerusalem.” It is still the epicenter of religious life for the heavily Orthodox Christian community.

To get to the churches, I had to buy a ticket—the only hint of tourist infrastructure in town. No one asked to see it. I entered a church at random. It was dark, lit by candles. It contained no pews, only worn rugs covering an uneven stone floor. The arched ceiling hung low. Heavy drapes divided the room into sections. It was unlike any house of worship I had ever been in. It felt primal. A few figures drifted by, staying close to the dark corners. By an altar, a priest in flowing garments stood over a woman who lay writhing on the ground. She was held down by two men and was wailing and moaning. The priest was snapping a wooden switch in the air and against the ground beside her. He spoke to her deliberately, strongly. I retreated a bit and then watched unabashedly. After a long while she was calm. I turned to go, and a man in white robes approached. “She is possessed by spirits, she needs to be cleansed,” he said. And he walked away.

I was told that to really experience the churches, I should return early the following morning, when the Mass was being said. After witnessing my first exorcism I wondered what could be next.

Before dawn the next day, I slipped into the first church I came upon in the maze of passages and was met by a powerful scent of incense, the air heavy with smoke. A few monks held beeswax candles; otherwise the small room was dark. Three priests read from Scripture. Shadowy figures crouched in corners. Chanting and drumming issued from an unseen room. To my Western eyes, it felt more like a scene to summon the devil than a place to worship God. I stood awkwardly by a wall. Then a young man leaned close to my ear and whispered, “Ticket.”

Since no one had asked to see it the day before, I had left my ticket back in my guesthouse. “In hotel,” I whispered apologetically.

“Ticket,” he repeated. Suddenly, I was unwelcome—very.

“Sorry,” I said, and turned to go. He seemed satisfied and retreated to the shadows. But I lingered just inside, near the door. The chanting grew louder. The priests began to sway left and right, and the drumming became more insistent. I felt a bit like Indiana Jones; I was far from home and loving it. Then the curtain covering the entrance beside me swung back and a silhouette filled the door. Lee Marvin.

I didn’t see his gun until we were outside. He ushered me uphill, toward I knew not where. A young boy fell in beside me. (Young children fell in beside me almost everywhere I went in Lalibela.)

“Where you from?” the child asked.

“America.”

“Obama!” he shouted.

I glanced over my shoulder at Lee Marvin, his gun pointed at my back. I thought his reaction to my offense was extreme; I tried to say as much. He grunted something in Amharic and prodded me with the tip of his rifle. I turned quickly back. I figured I wouldn’t be shot as long as I had a child by my side—I engaged the boy in animated conversation. Eventually we arrived at a green metal gate outside an official-looking building. Lee Marvin couldn’t open it. He grew frustrated, pulling at the padlock. From up the street, an older man with a beard arrived. Lee Marvin explained my offense, gesturing toward me with disgust. The man listened, and then turned to me. “Ticket,” he said.

I knew I had one chance. “Hotel,” I whimpered. I shrugged in shame.

He waved his hand in front of his face and I was free. Lee Marvin, incensed, began shouting. The boy said something and Lee Marvin raised his stick, but the bearded man put a hand to his shoulder. Lee Marvin turned his attention to me—he lifted a finger to just below his eye and then pointed it at me. I’d been warned. The older man led him away up the road. I tried to breathe.

AFTER MY BRUSH WITH THE LAW, it seemed like a good idea to keep a low profile for a while. I remembered a trail I’d noticed that ran out of town and up into the mountains.

I passed through blistered fields awaiting overdue rains. Hot wind blew, and dirt rose up in my face. Drooping oxen pulled broken plows through rock-littered fields. High up, I passed through a small village called Ashetem, set among a grove of eucalyptus trees—an oasis from the radiant heat. Here, a few hundred farmers tried to survive off the land, living in mud-and-stick homes.

Two young girls, perhaps 8 years old, came up to me. One of the girls wore a red dress, and her friend, maybe her sister, was in blue. With only their eyes, they asked for money, as so many children in Ethiopia had. I smiled and walked on. I was past them a few feet when the one in red said what sounded like the word “bottle.” I turned—I was carrying a now empty plastic water bottle. I held it up. She nodded. I stretched my arm toward her. Both girls leapt at it, grabbing it from my hand. They laughed and tugged. Then the laughing stopped but the struggling continued. I turned to go. After a dozen steps I turned back. The girl in red had won the battle and stood clutching her prize to her chest. She was staring directly at me, unblinking. Our eyes locked. A fly landed on my forehead. It seemed pointless to brush it away.

Back in town, I bought mango juice from a teenage girl at a small stand. I lay under a tree and tried to nap. I checked my phone, knowing it had no reception. I wondered why I was so far from home.

Near sundown I came upon a group of boys laughing and shouting. A raucous game of foosball was under way by the side of the road. I noticed the young boy who had come to my aid outside the church. Our eyes met and we smiled. He said something to his teammate and they welcomed me into their game, and we played, taking turns, laughing, until it was too dark to see.

There had been no power during my entire visit to Lalibela, and in the blackness my friend and I walked down the hill. Eventually he stopped and pointed off into the night, presumably toward where he lived. He offered me his hand; I shook it and watched him fade quickly into the dark. I continued on down the hill looking up into the blanket of stars, and following the Southern Cross, I found my way.