Lahinch Golf Club (Old)

AFTER A DECADE-LONG HIATUS FROM GOLF, THE AUTHOR FINALLY GIVES IN TO THE INEXORABLE PULL OF THE WILD IRISH LINKS THAT BEGAN HIS ORIGINAL INFATUATION WITH THE GAME

By Andrew McCarthy

WHAT WAS I THINKING? The wind is ripping in off the sea—the wind is nearly always ripping here. The undulating fairways, with few level landing areas, are running hard and fast. Deep pot bunkers lie in wait. The rough is dense, nearly two feet high in places. And I haven’t played a round of golf in almost a decade.

On a whim, 25 years ago, I had decided to join Lahinch Golf Club in the west of Ireland as an overseas member. My connection to the links gave me reason to return each year, an annual golf pilgrimage to renew my love of the game in a country where I had deep roots. But it was also here, at Lahinch, years later, that I walked off the 18th green and gave up the game.

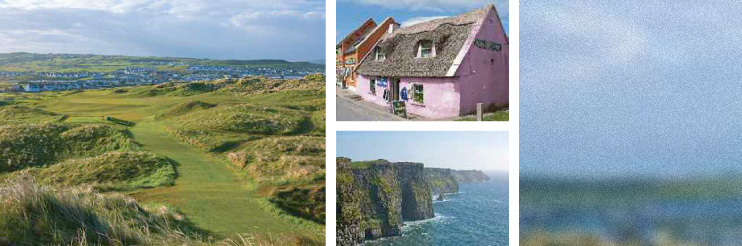

It had been just another lousy round in one of golf ’s most beautiful settings, the embodiment of “a good walk spoiled.” The rolling sea beside the course, with the fabled Cliffs of Moher visible just up the coast, as well as the subtle lure of the undulating land, were lost on me. I was miserable.

So without histrionics, I simply put away my clubs. I didn’t know then that my hiatus would last a decade. The longer my self-imposed exile continued, the harder it became to pick up a club.

The first time I played Lahinch, I felt as though I had found my home course (albeit 3,000 miles from home). Maybe it had something to do with the course’s pedigree—laid down by Old Tom Morris of St. Andrews in 1894, then redesigned in 1927 by Alister MacKenzie, who went on to design Augusta National and Cypress Point. Or maybe it was the easy welcome and unpretentious familiarity around the clubhouse. But I think it had more to do with the ground itself.

There’s a closeness to the land here, and a sense of privacy that descends amid the dunes, creating an intimacy between golfer and course that I’ve never experienced anywhere else. It’s been my overriding memory of this links all these years, and it’s part of what creates such devotion to Lahinch among so many.

When I walked away from the game, and Lahinch, I lost more than an annual holiday. My active investment in a place I felt such a deep affection for became a disconnected memory, and the insights the game regularly offered into my own psyche found no similar avenue of expression. I was simply a better person when I had golf in my life.

On top of that, I had heard that the links had undergone a major renovation, completed in 2003. What had they done to my course? The question haunted me. So before an offhanded decision became a permanent one, I decided it was time to come back.

Lahinch is a shotmaker’s course, where imagination is not only rewarded, but required. “You won’t play the same shot twice here,” promises Robert McCavery, Lahinch’s pro.

But that sense of imagination can border on bewilderment. On No. 4, a narrow landing area between high dunes sets the golfer up at the base of the large Klondyke, a tall dune that sits directly in the center of the fairway, making for a blind second shot over the hill. It was during my first round here, so many years ago, from the middle of the fairway, surrounded by nothing but raw dunes and long grass, that my playing partner demanded: “Where the hell is the course out here?”

And that’s nothing compared to the 5th. Dell is a 154-yard remnant of Old Tom’s original design. The green on the blind par 3 is tucked between massive dunes, invisible from the tee. A small white rock atop a tall dune—adjusted for pin placement—provides the only clue.

After a long ride, I arrive at Lahinch late in the day. Rather than wait for the next morning, I am eager to make my return to the game. So on the near-empty links, I tee off quickly. The prevailing onshore breeze (read, gale) takes my power fade (slice) well out into the fairway (the 18th). I take a one-putt triple bogey without seeing anything of the 1st hole other then the tee and green. At least that one’s out of the way.

MacKenzie strongly believed in honoring the land on which he designed, allowing the terrain’s natural contours and movement to dictate the layout. But the Lahinch course I knew and loved had been one that had been altered from MacKenzie’s original vision.

In the 1930s many of the greens were flattened and the course streamlined in an illadvised move. So Martin Hawtree was brought in to oversee the recent renovation. He promised “a restored MacKenzie course.”

Hawtree was as good as his word.

After 10 years, instead of looking different after the renovation, the course feels more deeply familiar because of the changes. The trusting of the original intent during the restoration has been rewarded. As I hack my way around in the wind, I experience a similar knowing about myself in relation to the game—and maybe in relation to much more than the game.

The greens—14 have been redesigned—now roll with the fall of the land. Teeing areas on 16 holes have been rebuilt, occasionally inviting power in places they didn’t before. A new par 3 was added, another redesigned, and four holes rerouted. Although slightly longer, the SSS (Standard Scratch Score) from the middle tees has gone from 71 to 73. The course lays itself out with intermittent audacity and confident subtlety by the sea.

I settle into bogey golf. At No. 18 I pull out the driver for the first time of the day and let rip. Finally, I hit it on the screws. My hands turn over, my hips release, and the ball sails true through the wind. I hold my finish and watch it fly.

Walking up the fairway, the late summer sun won’t quit, the wind is still blowing, and I’m grinning like a fool. I feel the golf hooks going back in, and I don’t mind.

After all, that sensation is what I came here for, what I hoped would happen. I three-putt my way to another bogey and know: I’ll be back next year.