Sleepless in Seville

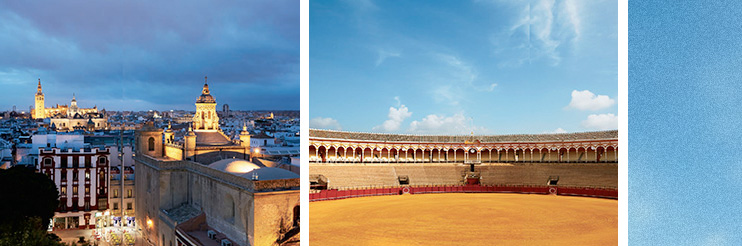

Returning to the capitaI of southern Spain, ANDREW MCCARTHY finds crowded Iate-night bars and restaurants, the passions of flamenco and buIIfighting, and the enduring mystery of the weeping Virgin.

By Andrew McCarthy

Outside the convent, for no reason, without thinking, I turn right. At the small Plaza de Pumarejo, in Macarena, a drunk is picking through the trash, mixing the remnants of discarded beer bottles like a waitress would marry jars of ketchup. A few feet away, a man has an easel propped up and is painting the church. An old lady with high, stiff hair is walking a small, puffy dog. I pass a fruit stand, a vintage clothing store, a hat shop. By the Almohad walls, which date from the 13th century, I walk into the basilica. There’s a wedding taking place; the first few pews are filled, the rest of the church is empty. I turn to leave, then turn back. There she is, above the altar. Her head encircled in gold filigree; her cloak encrusted with jewels; on her cheeks, crystal tears—the weeping Virgin.

Twenty years ago I passed through Seville for one night. Without my permission, a few random images snuck into my unconscious and lodged in my mind: a dark, narrow lane late at night that gave way to a tiny, jasmine-scented piazza; a thin young woman hitching up her long skirt to dance an impromptu flamenco in a crowded bar. And a photo I saw on the wall in a restaurant—the picture of a statue of the Virgin Mary with tear-stained cheeks. These accidental images became my experience of Seville and have, strangely, lingered as other seemingly more important recollections of cities and countries have faded. So I’ve come back, lured by a few mental postcards, for a closer look.

Situated in the fertile Guadalquivir River valley, just over 300 miles southwest of Madrid, Seville is the capital of Andalusia and the fourth-largest city in Spain, with a population of 700,000. Though its history dates back to Roman times, an invasion by the Moors in the eighth century left a cultural imprint that largely defines the city today. A few centuries later the Christian reconquest gave the city its massive cathedral; by the 1500’s, its river port was the center of trade with the New World—and Seville became rich. But when silt began to clog the river and shipping moved south to Cádiz, the city lost much of its clout. Thanks in large part to the creation of places such as architect Anibal Gonzalez’s Plaza de España, for the 1929 Ibero-American Expo, Seville began its long road back to cultural relevancy. The center of town today is a jumble of ancient, narrow lanes that follow no modern logic, yet Seville is an easy city to settle into.

“Here, it’s all about street living,” Patrick Reid Mora-Figueroa tells me. Together with his brother Anthony, Reid runs the Corral del Rey, a chic, low-key boutique hotel in a restored 17th-century palace. My room, in the annex adjacent to the main house, is a tasteful mix of reclaimed wood, contemporary linen fabrics, and discreet lighting. (The family also operates a rustic sister property 40 minutes to the south— the Hacienda de San Rafael, set amid fields of sunflowers on a former olive estate.)

“Very little entertainment happens in the home in Seville,” Reid says. “But try to get a party to leave their table at a restaurant in less than three hours, forget it. There’s a natural flow here.” And while many corporate businesses maintain conventional working hours, the daily rhythm of life in Seville—most of its shopping and dining—still carries on in the old ways. A late lunch is followed by an afternoon siesta, when most businesses shutter. Life kick-starts again after 9 p.m., when people take to the streets, often for a tapas crawl.

On one cloudless night, I start at El Rinconcillo, the oldest tavern in Seville, dating from 1670. Ornate Moorish tiles climb the walls, wooden casks hold the wine. Beside me, old men sip sherry. Overhead, on hooks hanging from the ceiling, are legs of the famous jamón ibérico. A hawklike waiter in white shirt and black vest slices paper-thin slivers of the deep, sweet, potent cured ham—Spain’s answer to prosciutto. He deposits each slice with reverence on a small white plate, then jabs the platter into the hand of another similarly clad waiter, who in turn shoves it in front of me. A third waiter, older and rounder, whips a thick piece of chalk from his pocket and scribbles the price directly onto the wooden bar in front of me, adding it to my running tab. This is as old-school as it gets.

Then, tacked up behind the bar, I see a calendar with the photo of a statue of the Virgin Mary—weeping. It’s the same image I saw so many years ago, the one that has lingered in my mind. It turns out that Our Lady of Hope (La Esperanza), a.k.a. La Macarena, is beloved throughout Seville. The statue is paraded in the streets and adored by thousands each year during Holy Week, before Easter. I will see a photo of the Virgin with the crystal tears in what seems like every restaurant and shop in Seville.

A few minutes’ walk away, just off the tiny Plaza de San Lorenzo, I find the other end of the tapas spectrum. Eslava, a hip, modern joint, draws a smart urban crowd that overflows onto a narrow street across from the Basilica de Nuestro Padre Jesús del Gran Poder. Pepe Suárez leads a happy staff behind the swarming bar.

“The tourists come early; the locals come late,” he says, delivering the house specialty, huevo sobre bizcocho de boletus (slow-cooked egg on boletus cake with a wine reduction). After another of those, then a green pepper stuffed with hake, then scallop over seaweed purée and kataifi noodles, I head to the nearby Bodega Dos de Mayo, where tables are spread out on the dimly lit Plaza de la Gavidia. The women still smoke, the men sip glasses of beer, and the kids race beneath orange trees. In the shadows, a solitary old man plays a mournful violin as a hot breeze blows through the night. Beside him is a large poster of a woman in a long red dress, castanets in hand.

Images of flamenco, the sensuous dance born in Andalusia, are everywhere in Seville. Red-and-white dresses with frilling trains fill shop windows; advertisements for shows are plastered on walls. The music and dance, identified as an “intangible cultural heritage of humanity” by unesco, is often dismissed as tourist enticement, yet there are many neighborhood bars where the locals get up and dance the sevillana, an erotic form of the dance done in pairs. There is even a flamenco museum, founded by legendary local dancer Cristina Hoyos.

Long, raven hair pulled back, piercing eyes set amid angular features, arms flung toward the heavens, feet stamping down, gathering power from the earth—if people unfamiliar with flamenco hold an image of the dance in their minds, it is probably one of Hoyos. Together with Antonio Gades, she helped bring flamenco to the world beginning in the late 1960’s.

“It is not necessary to understand flamenco,” she tells me, sitting among the interactive displays of her museum. “It must be felt.” The long black hair has gone an equally dramatic silver, and her eyes are still the mix of coy, flirtatious mischief and fiery resolve that captures the essence of flamenco. “In flamenco there is all of life. The joy, the sorrow. And it belongs to Andalusia, to Seville. This is a city that delights like a witch—why do you think Carmen is set here?—and flamenco is at the soul of Seville. It is a need for the local people; it was here long before tourism, and it will be here after.”

Across the river, in the working-class neighborhood of Triana, is where most of the local flamenco clubs lurk—shuttered until midnight, when the Cinderella dancers wake. Along the canal’s edge, in a storefront bar called Lo Nuestro, a lone guitarist strums a ferocious beat beside an idle bartender who unabashedly belts out a plaintive ballad to an empty room beneath the requisite picture of the weeping Virgin. By 3 a.m. the guitar is even more insistent, the bartender is too busy to sing, and the crowd is clapping and stomping along. Next door, couples are swirling in a passionate sevillana under the whirl of ceiling fans working hard—not hard enough. A few blocks away at Casa Anselma, an impromptu session has broken out in a sweaty room beneath antique flamenco posters and…the weeping Virgin.

Nowhere in Seville is the dramatic commingling of life’s suffering and glory more on display than at las corridas, or bullfights. It’s easy—and perhaps correct—to decry bullfighting as barbaric, as cruelty to animals of the highest order. But to grasp Seville in any real way, you must at least make an effort to come to terms with what los toros mean to Sevillanos.

“It is part of us. It is inside us,” Seville native Cristina Vega tells me from her family’s sombrerería on Calle Sierpes, the city’s pedestrian-only main shopping thoroughfare. “It would be a great loss for us if bullfighting were no more.” It’s the assumptive sentiment of many around town, one that I hear often. At festival times and on scattered evenings throughout much of the year, the local population gravitates toward the Plaza de Toros de la Real Maestranza, on the banks of the Canal de Alfonso XIII.

Before entering into the whitewashed cathedral of pomp and death, the spectators at nearby bars buzz in anticipation. A working-class crowd spills out onto Calle Adriano from Café-Bar Taquilla. Beer and excited chatter flow freely beneath the framed black-and-white photos of legendary bulls and famous toreros. On the way to his first bullfight, a young boy, no more than five, stands on a stool at a tapas bar beside his father, his chin rising just above the edge of one of the high tables, chomping on a plate of fried potatoes and ketchup. Around the corner, a more upscale crowd crushes elbows at Bodeguita A. Romero, a favorite venue for corrida aficionados. The well-dressed throng shouts orders from three-deep at the bar for rabo de toro (oxtail) and piripi (Seville’s answer to the BLT).

Once the 14,000 are packed inside, three toreros will each fight a pair of bulls over the next two hours. On this night it is las novilladas, young bullfighters making their early professional outings. The evening lacks the polish I’ve seen with more experienced bullfighters—although the prerequisite feline machismo is on full display. The famously discerning and notoriously demanding crowd is generous and appreciative of the novices.

Before his second bull, Juan Solís (“El Manriqueño”), a local boy who looks about 16, doffs his montera to the crowd and walks to the edge of the ring. He leans over the wall, speaking to an older man in the first row to whom he bears a striking resemblance. The young warrior’s face is earnest as he dedicates this bull to the man I assume to be his father or, at least, a mentor. When young Solís has finished his declaration, he offers the cap, with solemnity, to the man. Unapologetic tears pour down the older man’s cheeks. He makes no move to wipe them away as the boy with the red cape struts toward the heaving animal in the center of the dirt ring, sword in hand. Bullfighting may have become a dying and politically incorrect relic in many places—including parts of Spain—but on this night in Seville, it is deeply personal, and alive.

Like all places of real interest, Seville thrives on its contradictions. It can seem like a small town, yet I get lost daily along the narrow, misdirected lanes. It has a strong Catholic legacy, with the towering cathedral as its centerpiece, but so much of the city’s architecture and feel is decidedly Moorish. In the happenstance gatherings on street corners there is a strong provincial sense of life’s assurances, while the neighborhoods of Triana and Macarena have an edgy, evolving atmosphere. Restaurants such as Nikkei Bar, serving Japanese-Peruvian fusion, and the Slow Food establishment Contenedor, with its retro, urban-hipster vibe, are bringing new life, but nearby at the walled Monasterio de Santa Paula things are still rooted in the past.

I lift the old bronze knocker and let it fall against the heavy wooden door embedded in the high, whitewashed wall. After a few minutes the door creaks open and a tiny, heavily creased nun in full habit inspects the intruder. I’ve been told that the sisters make a sweet marmalade; I say as much. The nun nods. Unflattered, she silently admits me. I follow beneath a grove of orange trees, past the cloister, into a spartan, wood-paneled room. The sister reaches under the counter and produces a small jar.

“Three euro, eighty,” she tells me.

I have only a five-euro note and I hand it to her. The bill disappears under her garment; she offers me no change.

It’s then, outside the convent, after the heavy door slams behind me, that I move impulsively farther from the center of town, deeper into the daily life of Seville. I pass the drunk in the park, and the small man painting; gravitating without conscious thought to the Basílica de la Macarena. And while the young couple kneels before a priest to be married at the altar, I’m confronted with the weeping Virgin above the tabernacle.

Wandering the street, I didn’t know where I was headed; as I entered the church, I wondered why. Strangely, it never occurred to me to seek out the statue—which speaks perhaps to the ethereal, dreamlike presence the image has occupied in my mind since first seeing the photograph so many years ago. Yet encountering her now—all of a sudden, after so long—the sensation is that of discovering the familiar at last. Excitement and comfort, surprise and relief, delight and wonder all mingle. Maybe these feelings are elicited by my surroundings in the cavernous, ornate church; after all, these are among the sensations religion endeavors to evoke. But I think perhaps it’s something else. My passions, it occurs to me with satisfaction, stem from finally having kept my long-held date—with Seville.