Timeless Tastes

A sensational culinary quest for the perfect prosciutto in Italy’s Emilia-Romagna region

By Andrew McCarthy

The staircase is dark and narrow. The stone floor is worn smooth from six centuries of use. Before I duck my head to pass through the low arched doorway,the scent begins to overpower me. It is pungent, complex, and moldy—and this is one of only a handful of places in the world where it exists. It is why I am here. It’s the smell of excellence.

I’ve come to this part of Italy, about an hour-and-a-half drive south of Milan, on a simple mission—I’m here to eat. Prosciutto has been an obsession of mine since I first tasted the cured ham in Rome nearly a quarter-century ago.The sensuous texture, the sweet and potent taste, was unlike anything I’d known. It led me to all sorts of salumi— to coppa, and spalla, and fiocco.When I returned home to the States, I went to the best shops and paid high prices to get these Italian cured meats. They were good, but they couldn’t match the experience I fell in love with in Italy. So I’ve returned, this time to the epicenter of the prosciutto universe—to Parma.

Relishing Parma

Located in the region of Emilia-Romagna, deep in Italy’s Po river valley, Parma is an affluent city of more than 180,000. Unlike Rome, with its chaos, or Venice, with its otherworldly romance, Parma has an elegant, provincial ease; the feeling on the streets is of a privileged life unfolding with clear and predictable assurance. This is the home of Correggio and Toscanini—as well as some of the most discerning opera fans in the world. Cars are restricted from the centro storico (historic center), and the well-heeled natives parade the cobbled streets or peddle ramshackle bicycles with a disarming self-assurance.

“People from Parma are absolutely convinced they live in the best place in the world,” Melanie Schoonhoven, who came to Parma 20 years ago, assures me as we sip midmorning coffee at a sidewalk café on fashionable Piazza Garibaldi. “And because we get so few tourists compared with the rest of Italy, we’re happy to share it. And we certainly know how to eat.”

That’s a sentiment Parma native Andrea Aiolfi confirms. “Food will never abandon you here in Emilia-Romagna,” he tells me, munching a panino, an Italian sandwich, outside Antica Osteria Fontana, one of Parma’s classic enotecas. “It is our form of identity.”

My first Prosciutto di Parma—in Parma—is purchased from a local salumeria, a type of upscale delicatessen specially featuring the crudo. After buying some prosciutto, I find a seat on a stone bench in the nearly deserted Piazza del Duomo, beside the 12th-century pink-and-white-marbled Baptistery. Across the square, starlings circle and dive above the Romanesque cathedral, consecrated in 1106, as the purple sky fades into night. I unwrap the richly colored meat, with thin ribbons of white fat running through, and let its velvety texture linger on my tongue.

To ensure quality, a consortium closely limits and monitors the region’s prosciutto production. To be called Prosciutto di Parma, the hind leg of the pig must be sourced and aged within strict regional boundaries. In the verdant rolling foothills of the Apennine Mountains,the Castrignano Valley is home to most of the roughly 160 producers who aged nearly 10 million hams in 2011. Several local facilities offer public tours, and a visit to Salumificio Conti, above the town of Langhirano, reveals an ancient process aided only marginally by modern conveniences. Time is the primary component in producing the perfect prosciutto: For at least a year, in cool, shadowy rooms, the hams must dangle beside long windows that are periodically opened to allow the sea breezes that flow over the mountains to dry the meat.

Symbiotic Savor

One of the main components in producing succulent prosciutto is raising happy pigs, and nothing seems to keep them happier than the large quantities of whey they consume—a byproduct of Emilia-Romagna’s true culinary superstar. Despite the attention that cured ham commands in these parts, Parmigiano-Reggiano (Parmesan cheese)—also produced under tight regulation and within strict geographic boundaries—is the region’s most famous delicacy.

At Consorzio Produttori Latte, on the outskirts of Parma (one of a number of dairies open to visitors), I watch as the cheese is hauled from massive copper vats, then wrapped in raw linen and set in molds of willow wood before being placed in a salt solution, and ultimately stacked beside thousands of other wheels to age for at least two years. When I nibble a wedge of the rich and milky cheese, it bears little resemblance to the chalky stuff I get back home.

When a few drops of local balsamic vinegar are dripped on top of the crumbly Parmigiano,the taste is so surprising, so rich,that I find myself on the road, heading about 40 miles away along Italy’s Autostrada del Sole (Highway of the Sun; officially, A1) to Modena, the vinegar’s birthplace. Just outside the town, down a narrow road alongside fields of hay drying in the sun, past an iron gate at the end of a long drive flanked by soaring sequoias, I find Villa San Donnino.

Here, Davide Lonardi produces some of the finest Aceto di Balsamico (balsamic vinegar) in the world. “We produce only 170 liters per year,” says Davide, a wiry, shy man with a passion for his work. “It is a process I learned from my father, who learned from his father.”

All the grapes used for Davide’s balsamico are grown here, next to his villa—”So I can keep my eyes on them,” he says.

The potent smell of fermentation slams my senses as Davide leads me up to the 500 casks sitting silently in dim light under a low roof amid the attic’s stifling heat. For anywhere from 12 to 25 years, the vinegar develops in these wooden barrels, acquiring the properties that qualify it as Aceto Balsamico Tradizionale di Modena D.O.P. Here, too, a tightly controlled consortium oversees production specifications of the slightly more than 100 producers.

“This is the way it has always been done,” Davide assures me. “There are no additives.There is nothing, only time.”

When he offers me a few drops of the dark and syrupy liquid, it has a deep, complex taste that is closer to sweet than the acidic bitterness I’ve always associated with vinegar. And after he drizzles a few drops over a cup of ice cream, I buy three bottles.

L’Ultima

Back in Parma, I further indulge my salumi obsession. On Strada Farini,the place in town to see and be seen, Parmigianos sit at outdoor cafés, sipping aperitivos and nibbling cured meats. At Salumeria Rosi, the 18-month-old prosciutto has a sweetness that lingers; at nearby Gallo d’Oro, the coppa is potent and rich. And the prosciutto from La Verdi, on bustling Via Brigate Garibaldi, almost literally melts in my mouth. All are delicious, sensual experiences.Trying to find the best salumi in Parma is like trying to pick the most beautiful sunset in Hawai’i.

Then I begin to notice something on the menus of the finer restaurants and in the better shops— something called culatello.

“What’s culatello?” I ask a salumeria shopkeeper.

His eyebrows narrow as he leans over the counter. There is urgency in his voice when he whispers, “You have never tried the culatello?”

“Never,” I tell him. And when I do, there is no going back.

Like prosciutto, Culatello di Zibello is a cured ham made from the hind leg of the pig. Unlike prosciutto, culatello is made from only the choicest, meatier portion of the leg—the skin, bone, and much of the fat is removed before it is seasoned and hung in twine casing to age. It is widely accepted as the ultimate in salumi.

Soon I’m back on the road, heading to La Bassa—the lowlands—for an audience with the King: the king of culatello.

Past fields of corn and alfalfa, outside the tiny village of Polesine Parmense, on the humid banks of the Po river, I find Massimo Spigaroli at Antica Corte Pallavicina, a restored 14th-century castle, now a small inn and restaurant. Massimo’s family has been making culatello since his great-grandfather produced it for a local resident, composer Giuseppe Verdi.

“Only here, by the river,”Massimo tells me, “do we have the right climate for culatello.”

A stocky man with a wild gleam in his blue eyes, Massimo is part chef, part historian, part mad scientist. It is Massimo who leads me down the dark flight of twisting steps to the Holy Grail of salumi. And it’s here, before I turn the corner into the medieval cellar, that the intoxicating aroma of the aging ham stops me in my tracks.

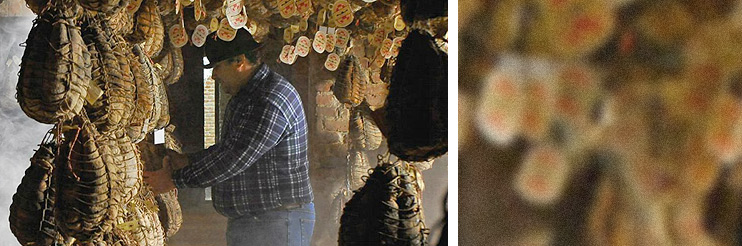

Just inside the dank room, the light is dim; nearly 4,000 pear-shaped bundles hang in satchels of twine from the low, vaulted ceiling. Some have already been spoken for—small signs with names like Armani and Principe Alberto II di Monaco hang from sacks in the corner.There is only one window, opened and closed on Massimo’s whim, to control the temperature and moisture allowed to contact his beloved culatello. Unlike prosciutto, which hangs virtually unattended for months, culatello must be constantly monitored, its location in the cellar shifted to ensure the creation of muffa nobile—the noble mold. “It is intuition,” Massimo says as he shrugs, “and experience.You must talk to culatello; it hears you.”Then he locks his eyes on me and raises a finger, “But you must know what to ask.”

Whatever Massimo has been asking his ham, it gives him the right answer. He offers me three different vintages, one aged for 18 months (sweet and delicate), one for 27 months (richer and more potent), and finally one aged 36 months—from his prize black pigs. The flavor of this culatello is smooth, mysterious, pungent, and delicious, like nothing I have ever tasted.

As the master returns to his kitchen, I savor the last of my culatello and watch the Po river roll silently past, as it has for centuries. For people like Massimo and Davide, food is a way to honor that past and carry its legacy into the future. Artisans who have devoted their life to their craft,they create an experience that goes beyond eating; it’s an embodiment of a local history and culture—the culture of Emilia-Romagna. On the way to my car, I glance quickly over my shoulder, and while the taste still lingers on my tongue, I slip back inside and down to the cellar—for one last whiff of perfection.